Octavia E. Butler was a citizen of the USA and a Black writer of science fiction. Her publishing career – just 14 books! – ran from 1970 to 2005.

In 2016 I decided to read all her work, in chronological order of publication. I had 13 books on my shelves, and was mostly rereading; some short stories and her last novel were still waiting to be read for the first time. I was interested to see how memory matched rereading, how the work stands up to the lapse of time, whether the reasons I had bought, read and valued them stand up to the test of time. How did I fare? How did the work fare?

* * *

‘Crossover’, only six pages long, was first published in Clarion in 1970. It’s a nicely atmospheric little horror story that I hadn’t read before. It’s told, with some dialogue, from the point of view of the protagonist, whose grasp of reality appears tenuous at best. I did not find it remarkable.

* * *

Patternmaster was next, and first novel, published in the US in 1976 and in the UK in 1978. It is a coming-of-age adventure story, featuring love, violence, death, disappointment and learning the world. Teray has just left school, to embark on his planned career as Patternist aristocrat. It all goes horribly wrong, and Teray is plunged into misery; his nurturing adults let him down; his friends betray him; he has no hope…

This is an aristocrat’s journey. The focus remains tightly on Teray’s single viewpoint, and we learn about the world of the story by following him. He does learn – an improbable amount very quickly; he does grow – arriving at maturity in an unfeasibly short period of fictional time; he encounters others – and his fellow-characters in the story are recognised as people, not just as props for the story. But although Teray loses his own privilege, and hangs out with slaves and others without privilege, he does not question his world, and the lessons he learns are about being a master in a world of masters and slaves.

Teray’s story ends when, adventure over, the young man has achieved his adulthood. But this is science fiction, and the writer created a world to tell her story in. There are psionic powers that enable practitioners to communicate and act at a distance, “mutes” (non-telepaths) as slaves and enemies, a post-holocaust landscape and society. Never mind Teray, the reader is left wanting to know more about that world.

* * *

Mind of My Mind was published in the US in 1977; my UK paperback was published by Sphere in 1980, under a superb cover by John Blanche.

The author of Crossover went on to publish Mind of My Mind: either’s characters could move between either’s neighbourhoods. In terms of genre, however, we pick up from Patternmaster, and find out how and where the Patternists came to exist, and why their social structures work they do. But it stops at the end of the beginning, leaving much unexplained.

In some ways both books tell the same story: like Teray, Mary has to fight her family – and particularly her father, Doro – to adulthood. But I found this a much more interesting book, for several reasons. It is still a story of a child coming to maturity, but it is a more interesting story, a more interesting child, and a more interesting maturity. There is a broader view of events, via the viewpoints of two protagonists, and a varied sample of the supporting cast. It’s clunky in places, and the pacing at the end is a bit off, but overall it is better written. And my knowledge of the future of this world sharpened my attention and deepened my appreciation for some of the details.

It’s set in that vague twentieth century suburban California that has cars and televisions and public schools, but pays no attention to any of these things. There is a strong strand of the science fictional conversation that is about finding your community in a hostile world, and this is a fine example: Butler’s focus is very tightly on her people, their individual desires and needs, and the relationships between them, and in setting up the world of the Patternists where they can feel at home.

It may have been startling to readers at the time of original publication that Butler’s protagonist is black and female, but although Mary is conscious of being black in a white world and female in a male world, and both matter enormously, those identities are not the fundamental drivers of the story. In Mary’s relationships with other people, gender and race are secondary relative to family, personality, competence and the struggle for power.

* * *

Survivor (1978) is the book that Butler later refused to have reprinted, according to Edward James.

The book is set in the Patternist universe, but there are no Patternists on the alien planet where human colonists, the Missionaries, have been settled for some years among the indigenous Garkohn. The Missionaries have become embroiled in the war between the Garkohn and their near neighbours, the Tehkohn.

The story is told through two viewpoints: wild human Alanna, a foundling child adopted by the Missionaries; and Diut, the Tehkohn Hao, the leader of his people. The book starts in the middle of the story, when Alanna returns to her people after some years among the Tehkohn, and the action flips back and forward between the past events that led to this point and the events from that point onwards. The story is quite satisfactory, although the manner of telling is sometimes confusing.

The family relationships between the characters are still the most important and convincing aspect of the story, but the background is much more strongly developed than in the previous two books, with attention paid to the relationships between the Garkohn and the Tehkohn as well as between both tribes and the Missionaries. This is Butler’s first attempt at building a world for herself rather than placing her characters in her own familiar California, and she makes a reasonable fist of it for the most part.

However, there are some problematic aspects today. The societies of the non-human Garkohn and Tehkohn are segregated by caste, and hierarchical, with caste and status conferred at birth. The non-humans are characterised as animals by the Missionaries, who believe that humans alone are made in the image of God. Relationships in both the human and non-human societies are patriarchal, and some are characterised by abuse. The issue is not that the story features these elements, but that these things are taken for granted, as it were, by both author and characters. At least some modern writers and readers no longer do take such things for granted. Is this the source of Butler’s later dissatisfaction with the book? Not impossible.

Notwithstanding all of this, there is a happy ending, of sorts for Alanna and Diut, which I feel suits the story well. And this feels like a better written book than the first two, more tightly plotted, structured and paced, and with convincing character and dialogue.

* * *

‘Near of Kin’ (1979) is a short story. The form is a dialogue between two people, with some of the thoughts of the narrator. The topic is parent/child relationships. After reading it twice I thought the gender of the narrator had been left undetermined. I read it a third time to confirm that the dialogue is specifically not gendered, and to find just two references in the narrator’s thoughts to being a little girl and daughter.

* * *

Kindred (1979) is the novel that made Butler’s name. (The novel is not related to ‘Near of Kin’.)

Kindred is the first book by Butler that I sharply remembered: a time travel story that takes the personal issues around time travel seriously; a woman who travels; a black woman who travels; a traveller whose experiences are realistic for her given origin and point of arrival; a strong female protagonist who is not a queen and does not become one. I remembered personal relationships of the past starkly contrasted with those of the 1970s. I remembered being shocked by some of the violence, both physical and emotional. I remembered putting the book down stunned by its power.

I reread the Pocket Books paperback edition, published in the US in 1981. (In the UK it was finally published in 1988, by The Women’s Press.) The front has this blurb:

“The stunning novel of a modern woman drawn into the cruel sensual world of the Antebellum South”

Kindred stands up to time and memory. That’s rare. Nearly four decades after publication, I did not stumble in reading it: no obsolete language, no unexamined assumptions, no stock backdrops distracting me from the story. I was rereading a remembered book, and it matched my memories, and nevertheless felt as fresh and shocking as if it were brand new.

More, I found that reading it was a physical act: whenever I put the book down I found myself aroused, with shallow breath and racing heart. And that isn’t because the story takes place in “the cruel, sensual world of the Antebellum South”; that’s because Butler’s unemphatic prose brings the reader calmly and surely into sympathy with the narrator, and you fear for her and her friends as you would fear for yourself and your friends.

Some of this book’s power as science fiction may arise from its challenging older fantasies of time travel, and of white, male dominance. Kindred is not like Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen (1965) by H. Beam Piper, or Lest Darkness Fall (1939) by L. Sprague de Camp, fantasies of the use of education and the rational mind to survive and take power in pre-Enlightenment societies. Nor is it like the old fantasies of male and slave-owning power: Mandingo (1957) by Kyle Onstott, or The Foxes of Harrow (1946) by Frank Yerby.

It must be unusual to read, or reread, Kindred now without at least some knowledge of Butler’s literary career in mind. I am amazed and astonished that this can be true for me and not destroy its power. I hope that is true for others coming to it for the first time.

* * *

Wild Seed (1980) is another Patternist novel. It tells Doro’s and Emma’s stories, and the origins of the Patternists, starting in pre-Christian Africa and ending in Twentieth Century California where it directly sets up the situation at the beginning of Mind of My Mind. It is written in much the same style as the earlier books, and presents the same mix of personal and family concerns that have been present in all the books so far. This one, however, gave me a much sharper recognition of the thematic links between the novels, both the ones previously published and the ones to come. I was reminded, in particular, of The Parable of the Sower (which was not published until 1993).

* * *

Clay’s Ark (1984). In a less-than-utopian future a century or so hence, humanity’s first starship, the Clay’s Ark, has returned from Proxima Centauri, its crew carrying a disease capable of wiping out the human race. The one survivor of the expedition knows this well, and is desperate to avoid the catastrophic outcome.

The action of the story is narrated through multiple viewpoints, male and female, and shifts back and forward in time between “past” and “present”. It takes place in the Californian desert, a nomansland where the rule of law is not an everyday feature of society. Butler keeps a tight focus on her viewpoint characters; the rest of the world is sketched lightly or not at all. And she is working with her familiar themes: the importance of family, the struggle to survive in a hostile world, and the clash between the interests of the indivdual and those of society. All well drawn and compelling, although in one or two places the shift of viewpoint is clumsily handled, and in others I cannot visualise and am not convinced by the events as described.

Although this is the story of the origins of the Clayarks, the relentless enemies of the Patternists, which would place it between Mind of my Mind and Survivor in that universe, the book stands alone.

* * *

Speech Sounds (1983) and Bloodchild (1984) both won Hugos, and Bloodchild won wide recognition elsewhere as well. I am not aware that I had ever read Speech Sounds before. Bloodchild is a different matter. I remember Bloodchild. I don’t think anyone who read it at the time could forget it.

I’m not surprised that the author of Speech Sounds wrote Clay’s Ark. Similar landscapes, similar elements: cars and roads, sex, violence, children, survival of the individual and the race. Similar question: how can you remain human when fundamental human characteristics are altered? They could almost (not quite) be set in the same world.

Bloodchild is different. The familiar elements are here, but mutated, altered. And there is also something new. Something alien. Both literally: alien persons (the Tlic) as characters in the story; and figuratively. It feels as if Butler has found something to say that she hadn’t said before, and that the rules for reading her stories have changed.

* * *

Next, a trilogy, published 1987-89, that features aliens. It also features ideas.

The Oankali are genetic engineers who wander among the stars seeking out new life forms to trade genetic material with. When they find a suitable host planet, they stay a while, organising themselves to make the trade. Humans will be superb trading partners.

There will be three groups of Oankali after the trade: The original pure strain Oankali, the Akjai, will travel onwards in the ship they came in. With them will travel the Toaht, one group of Oankali/Human hybrids. There will be another group of Oankali/Human hybrids, the Dinso, who will stay on Earth. But there will be no pure Humans. The Oankali know that Humans suffer from a fatal genetic contradiction, and the pure Human race must inevitably destroy itself. It would be cruel to permit this.

In Dawn the Oankali must persuade at least some humans to live and work with them and trade genetic material. They fail with some, but succeed with Lilith, who leads her people into relationship with the Oankali.

In Adulthood Rites, the childhood of Lilith’s part-Oankali son, Akin, is disrupted by violence and conflict, but through it Akin learns that pure humans, Akjai humans, must be allowed to survive. This is disruptive. It is cruel. The Oankali know it won’t work. The Humans don’t understand it. Only Akin could have that idea or convince others to implement it, but it is nevertheless inexorable, inevitable.

The third volume, Imago, follows Kindred in being written in the first person. This one does not have Kindred’s power, alas, although it has its moments. The story takes Jodahs, Lilith’s son and youngest child, from the brink of adulthood to some kind of maturity. We learn more about the Oankali, their drives, and their family relationships. We meet humans who have survived without interference from the Oankali, and learn about the cost of their survival.

The trilogy shows Butler exploring and developing new ideas. An example: human desire for sex and children has always been important, although taken somewhat for granted. Now these things are problematic, complicated, subject to discussion among the characters and interference by aliens. But not all the ideas are as well handled as the sex is.

I’m in two minds about this trilogy and the ideas it explores. The Oankali’s survival strategy is a powerful idea, but we’re focussed on the Dinso, the Oankali/Human hybrids remaining on Earth, and learn little of the Toaht or the Akjai. Butler works with ideas of leadership and consent in the first two books, but does not develop them in the third. Families comprise both species and three genders, but we learn little about the Oankali members of the mixed families, or any aspects of family life that individuals are not happy with. Lilith becomes the matriarchal leader of a mixed family, but we do not follow her life; instead the focus shifts to the children. Touch is very important, and we learn about characters through that sense, but other senses are not explored. I finish the trilogy wanting both more and less of it: less to appreciate the focus on the core idea; more to explore the many details left lacking.

* * *

‘The Evening, the Morning and the Night’ was published alongside Dawn in 1987, in Omni magazine, and deals with many similar themes. A young woman tells the story of how she met her prospective mother-in-law. Most of the words in the story deal with the personal and social impact of a very, very nasty hereditary disease, but it’s about family and leadership, and leadership in families, and the narrator’s fear of becoming what she seems destined to be. It was nominated for the Nebula.

* * *

There are two short non-fiction pieces in Bloodchild and Other Stories.

The first was originally published in 1989 as ‘Birth of a Writer’, but is reprinted under Butler’s preferred title of ‘Positive Obsession’ (which latter phrase also crops up in Parable of the Sower…). This is Butler’s own (brief, 14 page) account of her reading and writing life, also posing a question: “And what good is all this to Black people”. She talks about being a Black science fiction writer, and says: “Now there are four of us: Delany, Steven Barnes, Charles R. Saunders and me.”

Black is a word for an identity other than my own, that carries intimations of ethnicity, citizenship, and cultural affiliation. I’m not Black, but I relate directly to many aspects of Butler’s life as recounted here: as a member of a family; as a woman; as a reader; as someone ridiculed for being tall; as someone who “…has something that they can do better than they can do anything else” but has not yet found out what to do about that; all points of connection that bring me into sympathy with and help me to understand something about the rest. I’m glad I read this. I hope Butler would be pleased to know that her work has also been of use to people who are not Black.

‘Furor Scribendi’ (1993) is even shorter at just four pages, and is Butler’s advice for would-be writers.

* * *

Parable of the Sower was published in 1993. I read and reviewed it in 1994 (see my fanzine, Reflections in the Shards). Of all Butler’s books it is the one I remembered the best.

This is a first person female narrative, again, told in the form of journal entries written on the day of or shortly after the events described. This is very effective, and manages to be both direct and reflective at the same time. Lauren Olamina is the daughter of a Baptist preacher. She has teratogenic hyperempathy, the consequence of her mother taking a drug in pregnancy, which causes her to suffer sympathetic pain when she sees someone hurt. Olamina lives in a walled community in a disintegrating California. She has her fifteenth birthday at the beginning of the novel, on Saturday 20th July 2024.

The book is divided in two almost-equal halves. In the first half Olamina describes her community and way of life, frets about survival, and prepares to survive. In the second she is on the road, testing her theories on the dreadful world outside her walls. Olamina does pretty well, considering. Her theories work out better for her than she had any right to expect. There is a happy ending, of sorts.

Olamina covers much more ground than the characters in Clay’s Ark, which makes the similar absence of state or federal authority maintaining the peace more remarkable. There are no regulated refugee camps, no national guard. Difficult for this UK reader to accept when the USA is depicted as still functioning as a political entity.

This book must have had a greater effect on me than I understood at the time. Olamina has a theory of religion, she calls it Earthseed, and its essence is that God is Change. There is a passage where she explains her theory to one of her companions (pp199-202 in my first edition copy) that sets out very clearly the basis for how I think and act for myself. I wonder…did I take this from Butler wholesale? Wherever it came from, for her or for me, it is one of the great virtues of the book.

Notwithstanding the unrealistic aspects of the world Olamina describes, this is a very good book.

* * *

Parable of the Talents was published in 1998, and won the Best Novel Nebula in 1999. The blurb “…celebrates the usual Butlerian themes of alienation and transcendence, violence and spirituality, slavery and freedom, and separation and community, to astonishing effect…”

The story is told in two voices: Lauren Olamina’s journal gets most of the words, continuing the story from Parable of the Sower; but each section is introduced by her daughter, interjecting from an adult and divergent perspective. Both views are partial.

In Parable of the Sower the Earthseed community led by Olamina established a fledgling village. Now that community first prospers, and is then destroyed, and Olamina loses almost everything. At the start of the book we find out immediately that she has a daughter. At the end we know about both lives, and the relationship between them.

I read this book as conceived in anger.

Butler is angry with Olamina and her idealism and her previous easy ride: she destroys the first Earthseed community; puts Olamina through hell (again, and this time it is more personal); and makes her spend her entire, long lifetime doing her early-life’s work all over again.

Butler is angry with the brutality and hypocrisy of religion, and of men. And I mean men, not human beings. There is no female evil in the book.

Butler is angry with the United States of America: As a polity it fosters brutality and hypocrisy and persecution of the powerless, but prospers despite allowing these elements to flourish and never holding them to account. There is no enforcement of the laws that nominally protect Olamina’s people and property in this United States.

But above all Butler is angry at the family.

Family – born or made – has been the focus of Butler’s stories throughout her career. The Patternists make and break their families at Doro’s or Mary’s behest, and cannot rear their children in safety, but in doing so they do not betray each other. The proto-Clayarks need each other and feel an urgent need for each other. Kindred is in part an attempt to understand how members of a family can betray each other and still live together. The Tlic and the Oankali work with Humans to create mixed-species families that reconcile their differing interests in pursuit of survival. (And I’ll discuss Fledgling next.)

Here is the family whose members betray each other, and cannot live together. The father is absent, the mother cannot nurture her child, the brother cannot support his sister, the daughter cannot love her mother. And these are not temporary betrayals: these are permanent; they cut very deep and the wounds cannot be healed. Butler is angry with all of them: father, mother, brother, sister, daughter. And finds nought for their comfort or for hers in community or religion or polity.

And perhaps Butler is angry at herself too. Perhaps she got very caught up in Earthseed, and thinking that she could rely on family and community to be part of her solution for the future.

There are no easy answers here. Butler writes out much of her anger through the book, and at the end there is a grudging acceptance that things are as they are: recovery without justice; hope without foundation; survival without reliance on family as its bedrock.

* * *

Fledgling was published in 2005. The blurb says it “tests the limits of otherness and questions what it means to be human”.

Like Kindred and Parable of the Talents, this is a first person female narrative, in the past tense, but direct to the reader, without a framing journal. Shori, a fifty-three year old vampire, is the product of a genetic manipulation programme that separates her from her family. But she has just woken up with no conscious memories at all and doesn’t know who she is or why she is as she is. She acts on her instincts to survive and re-establish her identity. We learn who she is as she learns. Was this, perhaps, the way Butler could learn to write the alien?

Butler likes catastrophic adulthood rites, and here is another. It turns out that Shori-before-the-event was in fact still a child, and the events that have catapulted her into the story have also initiated premature adulthood. When she finds her family and her world again she can’t just settle back into childhood and being looked after. She must be an adult actor, tackling the issues around those events head on with more than her own survival at stake.

Here is yet another take on ideas of growing to maturity within a family. This one is analytical rather than taking families for granted. The issues of identity and trust that confront Shori are important to most of us in various ways, and Butler shows how they weave themselves into a sense of self, and literally gives them their day in court to be examined.

A familiar false note is that this is another book where family is sufficient to itself and the story. Once again, the mechanisms of the state that normally impinge on people’s daily lives do not trouble the characters, who can suffer or perpetrate the murder of family members and the destruction of property without attracting any interest from anybody interested in law enforcement.

Familiar concerns are extended into new areas: for example, the importance of touch and sex to the characters is familiar, but this time Butler pays attention to the sense of smell. As in the trilogy, new things are done well, but not always as well developed as they could be. Overall the book gains, with immediacy of action and even heightened emotion balanced by a somewhat reflective tone.

This is a story supremely well told. This is superb science fiction for the twenty-first century.

* * *

Afterwards, thinking about the whole work, how did we fare?

Both of us, Butler and I, fared very well. This was worth doing, for each book and individually, and for the whole. There are three books that I think deserve classic status, several more that are important and should be remembered, and none that failed my personal tests for a book worth reading now.

The five Patternist books are interesting as science fiction novels, particularly Mind of My Mind and Wild Seed, and I suspect stand well alongside their peers. As literature, however, I think I read a writer’s apprentice works, and if they were the sum of her work I would not particularly recommend their rereading.

Kindred was the literary masterpiece that integrated her skills and subjects and allowed her to move on. Kindred remains powerful and astonishing to this day, and should be remembered and reread for a long time to come. But it is still a part work, incomplete, leaving its travellers with a new understanding of their past and present, but not showing a way into their future.

The Xenogenesis and Parable books are about building futures in the wreck of the present. They stand individually as both science fiction and as literature, with Parable of the Sower as the best of them. But both series are incomplete, though I speculate for different reasons. Xenogenesis required Butler to write the alien, Oankali view, and perhaps she couldn’t find a way to do that? And notwithstanding the ending of Parable of the Talents, perhaps the series is incomplete because, knowing what she knew about humanity, Butler had lost faith in the future and maybe also in her own ability to write it?

After Parable of the Talents we waited seven years for Fledgling, Butler’s last novel. Here Butler again integrates her previous work into something new. She writes both the alien and a hopeful vision for the future. And puts both on trial. And concludes with judgement: both can go forward, though they must do so from a flawed and violent present. I think this is another classic to match Kindred on the shelves.

I wish that Butler had lived to give us more books. A writer this good who had found a hopeful future and a way to write about it would have been a prize worth having.

I am glad Butler lived to give us the books she did, and I’m glad that she is remembered.

Caroline Mullan

2016-2018

* * *

Bibliographical Note

ISFDB identifies 14 books published to 2014: 12 novels, and 2 collections. Butler’s page is here: http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?186

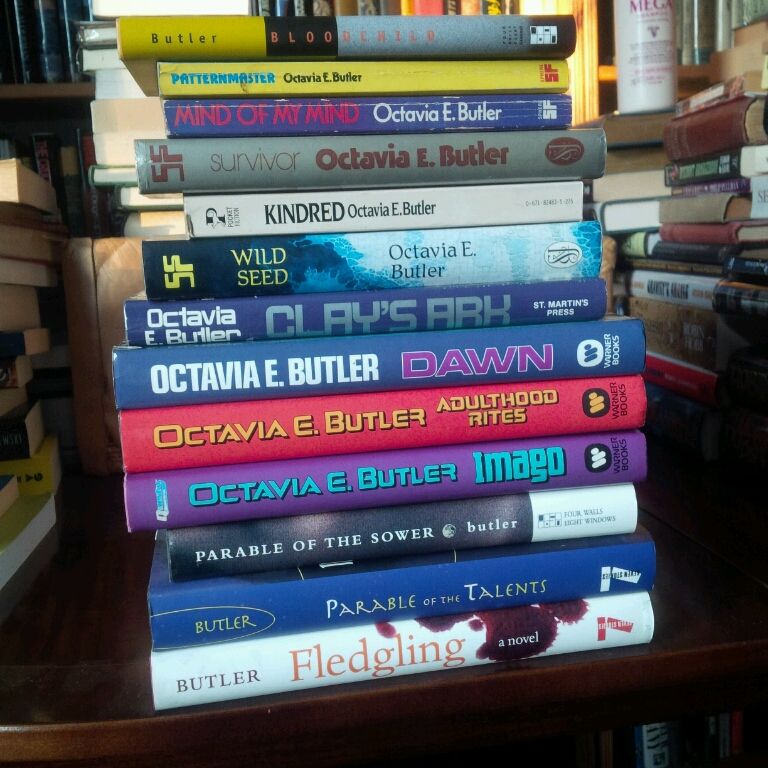

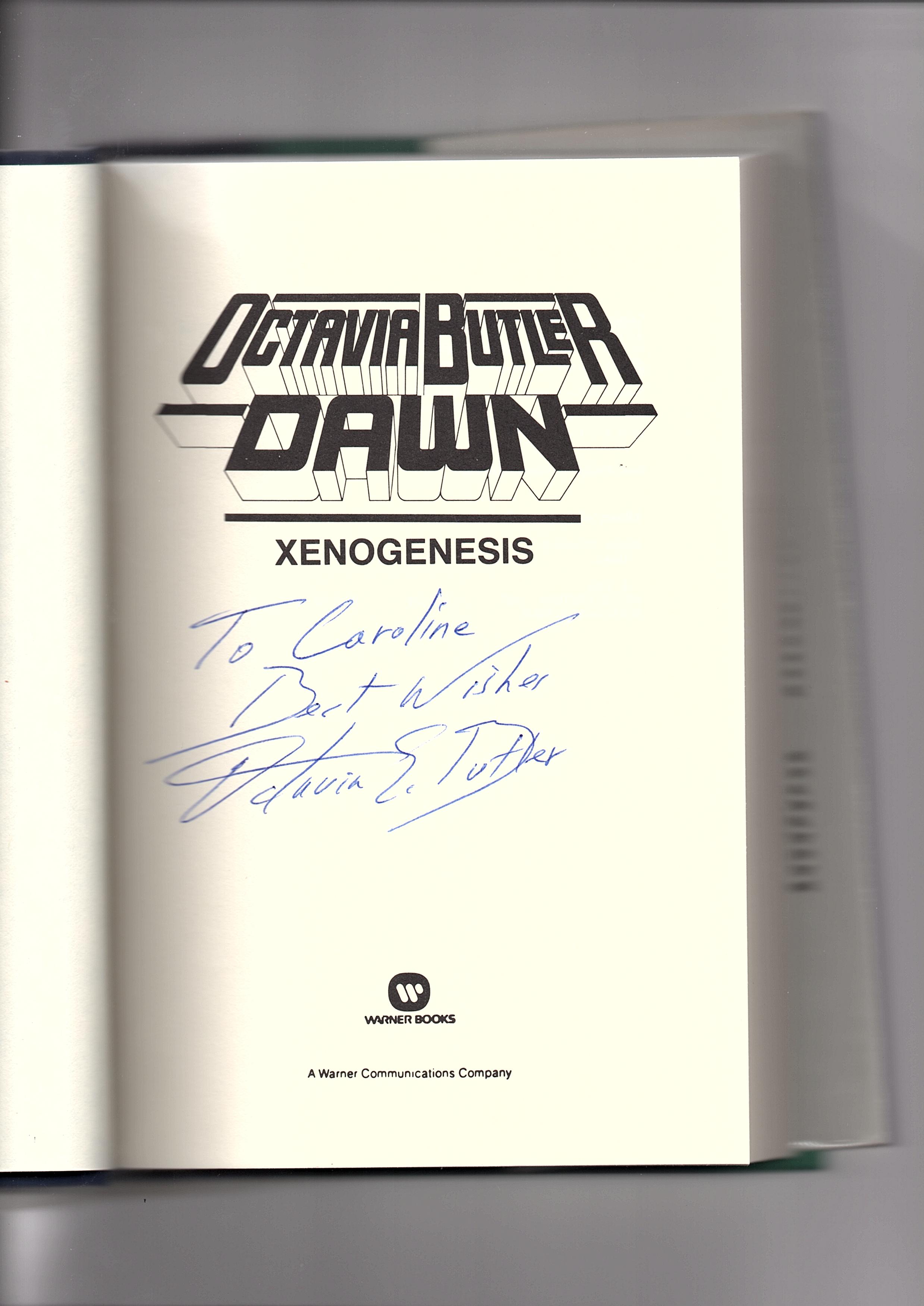

I read my own copies of her books, acquired randomly over many years, as you can see in the photo. Some are not first editions.

Bloodchild and Other Stories collects most of Butler’s very few short stories, with afterwords. I read each story in the first (1995) edition when appropriate to the chronology; a later edition in 2005 collects two additional stories from 2003 that I had not read when I wrote this.

Unexpected Stories was published in 2014 as an ebook. It has ‘Childfinder’, originally sold to but never published by Harlan Ellison in Last Dangerous Visions; and ‘A Necessary Being’. It was not available to me when I wrote this.

Many lists of Black science fiction writers have crossed my desktop in the past few years. Here’s one: https://list.ly/list/qe-black-science-fiction-writers.